A Practical Guide for Dendritic Cell Identification by Flow Cytometry

Written by: Sepideh Jahangiri, PhD in Experimental Medicine at Université de Montréal

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are essential orchestrators of the immune system, serving as critical antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that bridge innate and adaptive immunity. In the context of cancer, DCs play a pivotal role in recognizing tumor-associated antigens, processing them, and presenting them to T cells to initiate an anti-tumor immune response. Through the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and cytokine secretion, DCs activate cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) or regulatory T cells (Treg) (Figure 1.). Given DC’s critical function and susceptibility to tumor-induced dysfunction, accurately identifying and quantifying DC subsets within tissues is imperative for understanding tumor immunology and evaluating responses to immunotherapies. To dissect the complexity of DC biology, immunophenotyping by flow cytometry remains the gold standard. This high-dimensional technology enables researchers to identify and characterize DC subsets with precision, offering insight into their roles across tissues and disease states.

Figure 1. How DCs coordinate CD4 and CD8 T cell anti-tumor immune responses, published in Alfei et al, 2021, and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License [1].

Understanding Dendritic Cell Subsets

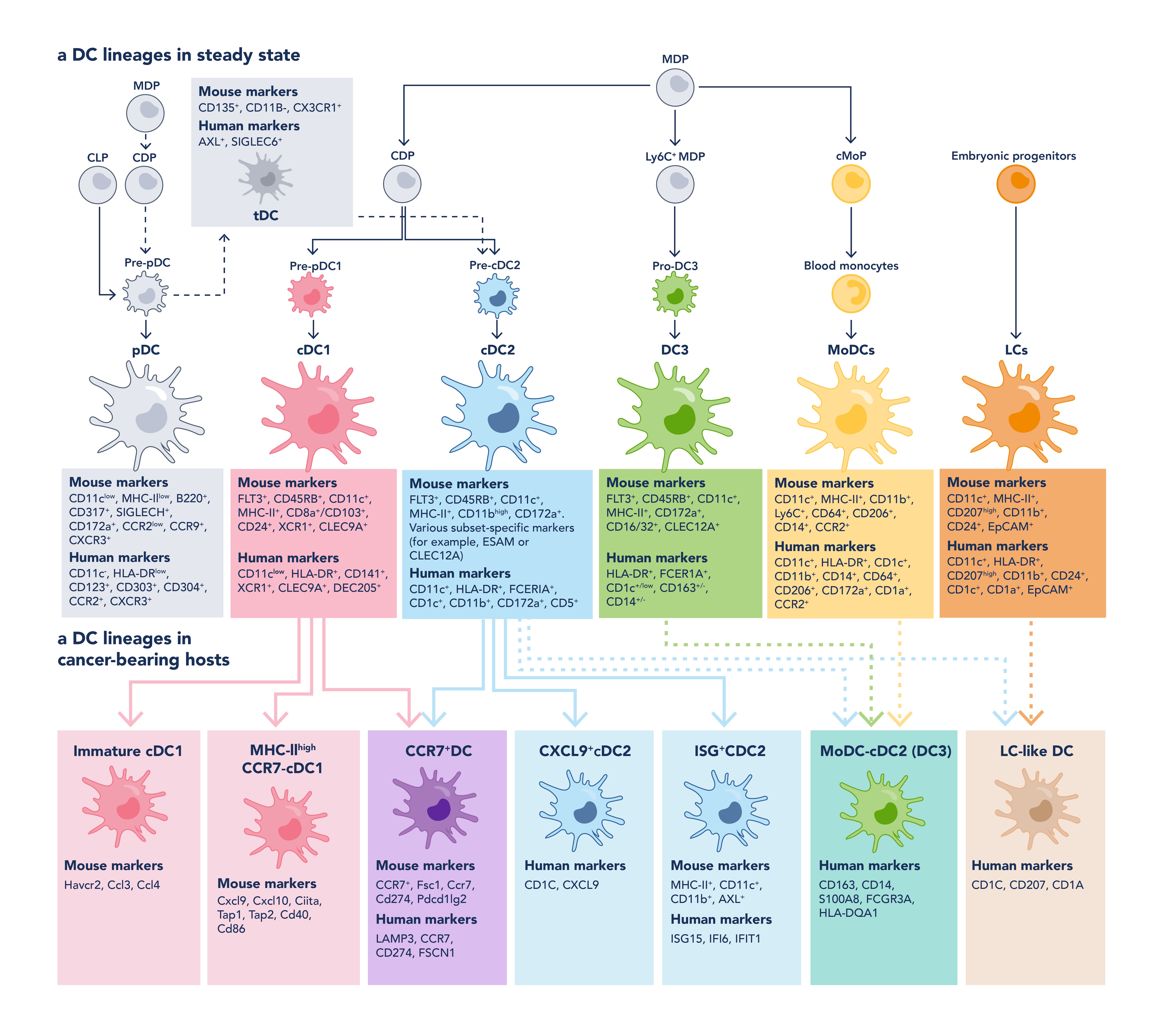

DCs comprise a heterogeneous family of immune cells that differ in ontogeny, phenotype, and function. Broadly, DCs can be categorized into several major subsets, each with distinct markers and roles in immune regulation, particularly in cancer and inflammation (Figure 2).

Conventional Dendritic Cells (cDCs)

cDCs arise from common dendritic cell progenitors (CDPs) in the bone marrow and are typically divided into cDC1 and cDC2 subsets:

-

cDC1s are a transcriptionally homogeneous population specialized in antigen cross-presentation. They are characterized by markers such as CD11c+ and CD8α+ in mice or CD141+ (BDCA-3) in humans. Within the tumor microenvironment, high cDC1 gene signatures are associated with increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells [2, 3], correlating with improved prognosis and better responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors [4, 5].

-

cDC2s are phenotypically and transcriptionally more diverse. They excel at cytokine production and are crucial for CD4+ T cell priming. Markers include CD11c+ and CD11b+ in mice or CD1c+ (BDCA-1) in humans. Recent studies distinguish CDP-derived cDC2s (often expressing CD5 in humans or ESAM in mice) from DC3s, a non-conventional subset that expresses CD14 and/or CD163 in humans and arises from monocyte–DC progenitors. The prognostic value of cDC2s is context-dependent: they are associated with favorable outcomes in cancers such as breast and head and neck cancer [5], but may indicate poorer prognosis in others, like non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [6].

Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells (pDCs)

pDCs are primarily known for their robust type I interferon (IFN-I) production. They are characterized by CD123+ and CD303+, typically lacking CD11c expression. While pDCs are generally inefficient APC in the tumor setting, upon proper ex vivo activation and reinfusion, they can drive potent tumor-specific T cell responses, particularly in melanoma [7]. Their presence in tumors has been associated with both favorable and unfavorable prognoses depending on the cancer type and activation status.

Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells (moDCs)

moDCs differentiate from infiltrating monocytes under inflammatory or pathological conditions, such as cancer. These cells express markers like CD11c+, CD14+, CD80+, and CD86+. Although generally considered less immunostimulatory than cDCs, moDCs can still elicit antitumor T cell responses in certain contexts [8]. However, intratumoral gene signatures derived from in vitro-generated moDCs have shown limited prognostic relevance in most cancer types.

Transitional and Tissue-Specific DCs

Other subsets such as transitional DCs, which exhibit features of both pDCs and cDC2s [9, 10], and Langerhans cells, which originate from embryonic progenitors but exhibit DC-like antigen-presenting capacity, further highlight the diversity of the DC compartment [11].

Therefore, understanding the developmental origin and phenotypic markers of each DC subset is essential for accurate immune profiling. Their distinct roles in antigen presentation, cytokine secretion, and T cell activation underscore the need for precise identification and quantification, where DC subset abundance and function have significant prognostic and therapeutic implications.

Figure 2. The heterogeneous family of DC subsets with their markers in mouse and human, adapted from Heras-Murillo, I. et al, 2024 [12].

Designing a Flow Cytometry Panel for DCs

Designing a robust flow cytometry panel for DC identification requires careful planning to ensure accurate, reproducible results, especially given the complexity and heterogeneity of DC subsets. When building a multicolor panel, several key considerations must be addressed:

-

Fluorophore Compatibility: Select fluorophores based on your flow cytometer’s laser configuration. Avoid spectral overlap between fluorophores with similar emission spectra by using tools such as spectral viewers and fluorophore brightness charts. To do so, always check your list of fluorophores with Proteintech’s spectra viewer.

-

Compensation Requirements: Prepare single-stained controls for each fluorophore to correctly compensate for spillover and always include unstained and fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls to set accurate gates.

-

Tissue Source: DC subset abundance and marker expression vary significantly between tissues (e.g., spleen vs. tumor vs. blood), influencing both antibody choice, fluorophore brightness, and gating strategy. Tissue processing (e.g., enzymatic digestion) can also affect epitope stability.

For a more in-depth overview of best practices in panel design, consult Proteintech’s comprehensive guide to flow cytometry panel building and our flow cytometry workshop.

Accurate DC identification by flow cytometry begins with high-quality sample preparation. The integrity of surface markers and cell viability directly affects downstream staining and data reliability, especially when working with delicate or low-abundance immune subsets like DCs.

Tissue Processing

Dendritic cells are commonly isolated from tissues such as spleen, lymph nodes, tumors, and blood. Mechanical disruption alone is not sufficient; enzymatic digestion is often necessary to liberate DCs from tissue matrices. However, excessive enzymatic treatment can degrade surface markers.

-

Use gentle enzymatic digestion with reagents like collagenase D and DNase I to dissociate tissue while preserving epitopes critical for antibody binding.

-

Keep cells on ice post-digestion and work quickly to minimize activation or degradation.

Blocking and Staining

-

Before staining, block Fc receptors using anti-CD16/32 (for mouse samples) or commercial human Fc receptor blockers to prevent nonspecific antibody binding. Alternatively, use Fc-silenced antibodies such as FcZero-rAb.

-

For DC phenotyping, surface staining is typically sufficient. Use fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies targeting markers like CD11c, CD8α, CD11b, CD123, CD80/CD86, and MHC II.

-

For functional studies involving cytokine expression or transcription factors, include fixation and permeabilization steps for intracellular staining.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Once your cells are stained, proper data acquisition and analysis are essential for accurately identifying dendritic cell subsets and assessing their activation status. A well-thought-out gating strategy ensures precision and reproducibility in your experiments. There are several analyzing platforms, such as FlowJo, FCS Express, and Cytobank.

Gating Strategy

Use a stepwise gating approach to exclude artifacts and home in on your population of interest:

-

FSC/SSC gating to remove debris, localized in a highly dense corner of the graph

-

Single cell discrimination to exclude aggregates

-

Viability dye exclusion to gate on live cells

-

Lineage exclusion (e.g., CD3-, CD19-) to remove T and B cells

-

CD11c+ selection to define total DCs (pDCs lie in CD11c-)

-

Subset gating based on CD8α, CD11b, CD103 (murine) or CD1c, CD123, CD141 (human)

Proteintech offers expertly designed antibody panels tailored for identifying a wide range of immune cells. Let your flow cytometry experiments capture the complexity and elegance of dendritic cell biology.

Example: Mouse Dendritic Cell Subset Profiling Panel

|

Fluorochrome |

Catalog No. |

Target |

Clone / Reactivity |

Subset |

|

CoraLite® 594 |

65130-1-Ig |

Mouse |

cDC (general) and Mo-DC |

|

|

Atlantic Blue |

65069-1-Ig |

Mouse |

cDC1 |

|

|

CoraLite® Plus 555 |

65055-1-Ig |

Mouse; Human |

cDC2 |

|

|

CoraLite® Plus 647 |

98020-1-RR |

Mouse |

Mo-DC |

|

|

PE |

65076-1-Ig |

Mouse |

Mo-DC |

|

|

CoraLite® Plus 488 |

65139-1-Ig |

Mouse |

pDC |

|

|

FITC Plus |

98225-1-RR |

Mouse |

pDC |

|

|

CoraLite® Plus 750 |

98025-1-RR |

Mouse |

Mature marker |

References:

-

Alfei, F., P.-C. Ho, and W.-L. Lo. DCision-making in tumors governs T cell anti-tumor immunity. Oncogene, 2021. 40(34): p. 5253-5261.

-

Barry, K.C., J. Hsu, M.L. Broz, F.J. Cueto, M. Binnewies, A.J. Combes, A.E. Nelson, K. Loo, R. Kumar, M.D. Rosenblum, M.D. Alvarado, D.M. Wolf, D. Bogunovic, N. Bhardwaj, A.I. Daud, P.K. Ha, W.R. Ryan, J.L. Pollack, B. Samad, S. Asthana, V. Chan, and M.F. Krummel. A natural killer–dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy–responsive tumor microenvironments. Nature Medicine, 2018. 24(8): p. 1178-1191.

-

Broz, M.L., M. Binnewies, B. Boldajipour, A.E. Nelson, J.L. Pollack, D.J. Erle, A. Barczak, M.D. Rosenblum, A. Daud, D.L. Barber, S. Amigorena, L.J. Van't Veer, A.I. Sperling, D.M. Wolf, and M.F. Krummel. Dissecting the tumor myeloid compartment reveals rare activating antigen-presenting cells critical for T cell immunity. Cancer Cell, 2014. 26(5): p. 638-652.

-

Mastelic-Gavillet, B., A. Sarivalasis, L.E. Lozano, T. Wyss., S. Inoges, I.J.M. de Vries, F. Dartiguenave, P. Jichlinski, L. Derrè, G. Coukos, I. Melero, A. Harari, P. Romero, S. Viganó, and L.E. Kandalaft. Quantitative and qualitative impairments in dendritic cell subsets of patients with ovarian or prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer, 2020. 135: p. 173-182.

-

Michea, P., F. Noël, E. Zakine, U. Czerwinska, P. Sirven, O. Abouzid, C. Goudot, A. Scholer-Dahirel, A. Vincent-Salomon, F. Reyal, S. Amigorena, M. Guillot-Delost, E. Segura, and V. Soumelis. Adjustment of dendritic cells to the breast-cancer microenvironment is subset specific. Nature Immunology, 2018. 19(8): p. 885-897.

-

Tabarkiewicz, J., P. Rybojad, A. Jablonka, and J. Rolinski. CD1c+ and CD303+ dendritic cells in peripheral blood, lymph nodes and tumor tissue of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology Reports, 2008. 19(1): p. 237-243.

-

van Beek, J.J.P., G. Flórez-Grau, M.A.J. Gorris, T.S.M. Mathan, G. Schreibelt, K.F. Bol, J. Textor, and I.J.M. de Vries. Human pDCs Are Superior to cDC2s in Attracting Cytolytic Lymphocytes in Melanoma Patients Receiving DC Vaccination. Cell Reports, 2020. 30(4): p. 1027-1038. e4.

-

Wculek, S.K., F.J. Cueto, A.M. Mujal, I. Melero, M.F. Krummel, and D. Sancho. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2020. 20(1): p. 7-24.

-

Villani, A.-C., R. Satija, G. Reynolds, S. Sarkizova, K. Shekhar, J. Fletcher, M. Griesbeck, A. Butler, S. Zheng, S. Lazo, L. Jardine, D. Dixon, E. Stephenson, E. Nilsson, I. Grundberg, D. McDonald, A. Filby, W. Li, P.L. De Jager, O. Rozenblatt-Rosen, A.A. Lane, M. Haniffa, A. Regev, and N. Hacohen. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science, 2017. 356(6335): p. eaah4573.

-

Sulczewski, F.B., R.A. Maqueda-Alfaro, M. Alcántara-Hernández, O. A. Perez, S. Saravanan, T.J. Yun, D. Seong, R. Arroyo Hornero, H.M. Raquer-McKay, E. Esteva, Z.R. Lanzar, R.A. Leylek, N.M. Adams, A. Das, A.H. Rahman, A. Gottfried-Blackmore, B. Reizis, and J. Idoyaga. Transitional dendritic cells are distinct from conventional DC2 precursors and mediate proinflammatory antiviral responses. Nature Immunology, 2023. 24(8): p. 1265-1280.

-

Segura, E., Human dendritic cell subsets: An updated view of their ontogeny and functional specialization. European Journal of Immunology, 2022. 52(11): p. 1759-1767.

-

Heras-Murillo, I., I. Adán-Barrientos, M. Galán, S.K. Wculek, and D. Sancho. Dendritic cells as orchestrators of anticancer immunity and immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2024. 21(4): p. 257-277.

Related Content

The power of neutrophils: How to identify the immune system’s first responders | Proteintech Group

Guide to Flow Cytometry Panel Building | Proteintech Group

Flow Cytometry Gating for Beginners | Proteintech Group

Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells (HSPCs): What They Are and How to Identify Them | Proteinte…

Support

Newsletter Signup

Stay up-to-date with our latest news and events. New to Proteintech? Get 10% off your first order when you sign up.